How can Hate Speech be countered in India?

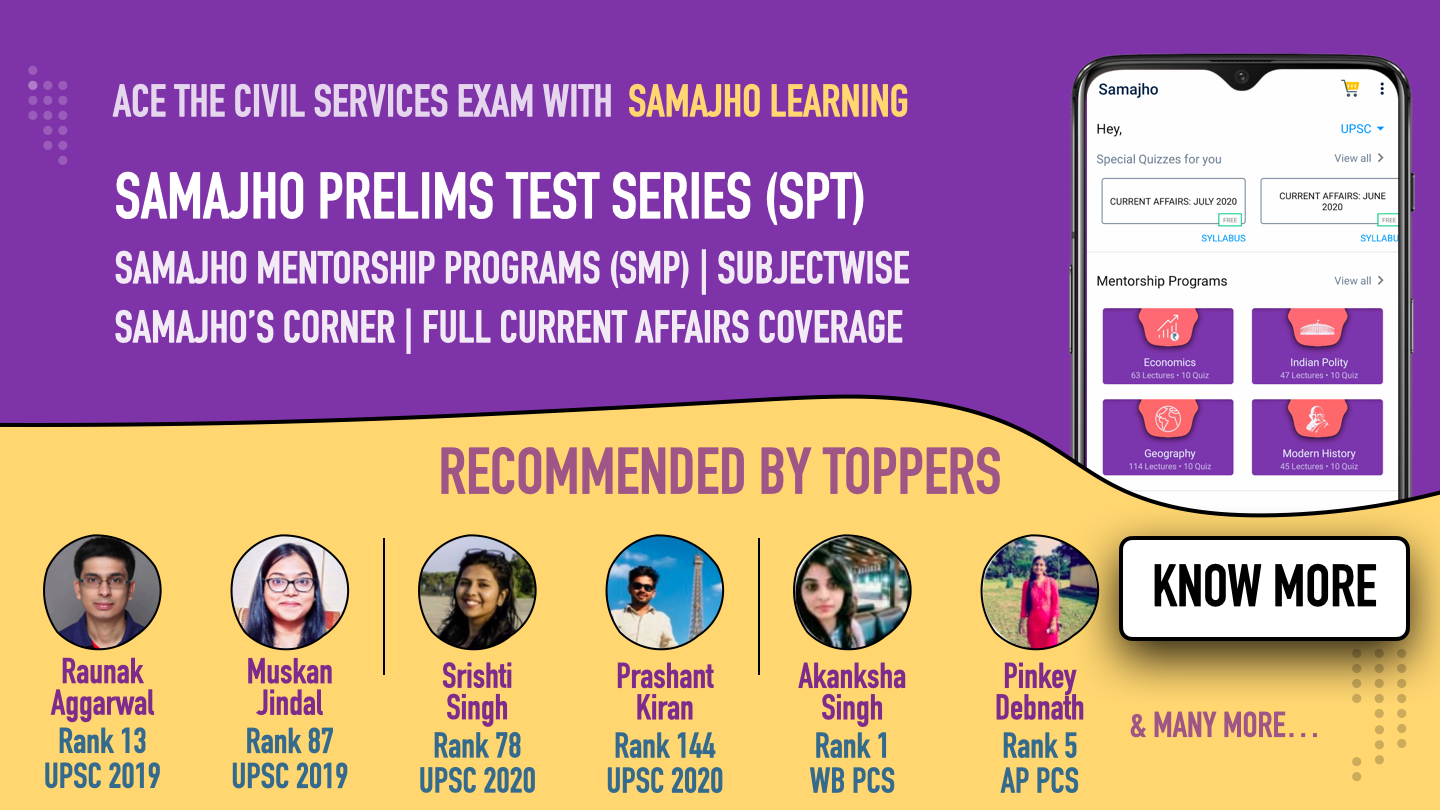

This article was originally a part of Samajho's Corner Premium Content but has been unlocked for you to assess our quality of content..

Join Samajho's Corner Now to get full access to all Premium Articles for 18 months.

Context: Recently, an FIR was filed against a leader in Uttarakhand for promoting enmity amongst different sections of society. In this article, we will understand how free speech is different from hate speech and the reasons behind the rising frequency of hate speech in India. We will also discuss the manner in which the cases of hate speech can be countered from an Indian perspective.

Relevance:

- Prelims: Sections 505(1) and 505(2), Article 19(1) (a), Representation of People’s Act, 1951 (RPA), Shreya Singhal v. Union of India.

- Mains: GS Paper – 2 & Government Policies & Interventions, About Hate Speech, Reasons of increasing hate speech in the Indian Society and steps that can be taken to tackle these kinds of issues.

| What is Hate Speech? |

- Hate speech is neither defined in the Indian legal framework nor can it be easily reduced to a standard definition due to the myriad forms it can take.

- Black’s Law Dictionary has defined it as “speech that carries no meaning other than the expression of hatred for some group, such as a particular race, especially in circumstances in which the communication is likely to provoke violence.”

- Building on this, the Supreme Court, in Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan v. Union of India (2014), described hate speech as “an effort to marginalise individuals based on their membership in a group” and one that “seeks to delegitimise group members in the eyes of the majority, reducing their social standing and acceptance within society.”

| How is Hate Speech defined by various organizations/institutions |

- According to European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), Hate speech covers many forms of expressions that advocate, incite, promote or justify hatred, violence and discrimination against a person or group of persons for a variety of reasons.

- In the 267th Report of the Law Commission of India, hate speech is stated as an incitement to hatred primarily against a group of persons defined in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religious belief and the like.

- According to United Nations, the term hate speech is understood as any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factors. This is often rooted in, and generates intolerance and hatred and, in certain contexts, can be demeaning and divisive.

- European Convention on Human Rights: Similarly, Article 10(2) of the European Convention on Human Rights, provides reasonable duties and restrictions during the exercise of one’s fundamental right to free speech.

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR): As per Article 19(3) of the ICCPR, the right of freedom of speech can be regulated in order to honour the rights of others and in the interest of public order, public health or morals.

- Article 20(2) of the ICCPR also declares that any advocacy of national, racial, or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prevented by law.

| Legal framework/provisions governing hate speech in India |

- Under Indian Penal Code:

- Sections 153A and 153B of the IPC: Punishes acts that cause enmity and hatred between two groups.

- Section 295A of the IPC: Deals with punishing acts that deliberately or with malicious intention outrage the religious feelings of a class of persons.

- Sections 505(1) and 505(2): Make the publication and circulation of content that may cause ill-will or hatred between different groups an offence.

- Under Representation of People’s Act:

- Section 8 of the Representation of People’s Act, 1951 (RPA): Prevents a person convicted of the illegal use of the freedom of speech from contesting an election.

- Sections 123(3A) and 125 of the RPA: Bars the promotion of animosity on the grounds of race, religion, community, caste, or language in reference to elections and include it under corrupt electoral practices.

- The Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (Prevention and Control) Act, 2017 (HIV/AIDs Act) is aimed at the welfare of people suffering from AIDS/HIV by prohibiting behavioural discrimination along with social stigma towards them. Section 4 of this act specifically aims for such protection.

- The Cinematography Act, of 1952 governs the exhibition of cinema framing various laws that provides power to the state to take actions against such an exhibition of cinema.

- Speech directed by any person who himself is not a member of SC or ST community towards the SC or/ and ST community to demean them and hurt them is prevented from occurrence under the Prevention of Atrocities Act, 1989.

| Free Speech vs Hate Speech- a constitutional perspective |

- The Constitution of India provides the right of freedom, given in article 19 with the view of guaranteeing individual rights that were considered vital by the framers of the constitution. The right to freedom in Article 19 guarantees the freedom of speech and expression, as one of its six freedoms.

- However, under Article 19(2), the constitution also provides for the reasonable restrictions against free speech in the interests of sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence.

- Why is there a tussle between freedom of speech and social media regulation?

- Until the advent of social media, adequate forums to express oneself existed, notably the radio, print media, or television.

- The prerogative of these platforms was to decide on the content they published. In effect, the content was subject to pre-approval of the relevant medium.

- Hence, if private media refuses publication of a citizen's views, the citizen cannot enforce its fundamental right against a private party. It is only when the state imposes restraints that go beyond Article 19(2), does the citizen have a remedy against the state.

- While traditional media acted as publishers and retained control over what gets published, social media platforms have chosen to position themselves merely as technology platforms. Thus, there is no pre-approval for content published on these platforms.

- When the government or courts order takedown of content, the aggrieved citizen can invoke their fundamental rights and approach the court to protect their freedom of speech.

- When platforms (being private, non-state entities) themselves take down the content, the aggrieved citizens feel helpless as they cannot enforce fundamental rights against a private party (in this case, platforms).

- In some cases, the government itself asks the platforms to take down certain content or ban some social media accounts, if they are seen to be spreading violence, misinformation or fake news.

- How does social media aid hate speech?

- Unregulated information sharing on the platform: As exposed in a report by an international media organization, Facebook is symptomatic of a larger infection of unregulated information dissemination through social media.

- Hate speech against Rohingya minorities: A Reuters investigation found that Facebook didn’t appropriately moderate hate speech and genocide calls against Myanmar’s Rohingya minorities.

- Prioritize business interest over common good: It is even accused of conducting a psychological experiment on its user’s emotions and more aspects of their personality. For example, Recently Facebook was accused of conducting a psychological experiment on its user’s emotions and more aspects of their personality.

- Insensible approach: Google has been accused of delaying the removal of malicious content even after volunteer groups had reported it.

| Judicial perspective on Hate Speech |

- The Supreme Court, in State of Karnataka v. Praveen Bhai Thogadia (2004), emphasised the need to sustain communal harmony to ensure the welfare of the people.

- In the Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan case, the Supreme Court underlined the impact hate speech can have on the targeted group’s ability to respond and how it can be a stimulus to further attacks.

- In G. Thirumurugan Gandhi v. State (2019), the Madras High Court explained that hate speeches cause discord between classes and that the responsibility attached to free speech should not be forgotten.

- Summing up these legal principles, in Amish Devgan v. Union of India (2020), the Supreme Court held that “hate speech has no redeeming or legitimate purpose other than hatred towards a particular group”.

- Lack of established legal standard: Divergent decisions from constitutional courts expose the lack of established legal standards in defining hate speech, especially those propagated via the digital medium.

- Arup Bhuyan vs the State of Assam: The Court held that a mere act cannot be punished unless an individual resorted to violence or incited any other person to violence.

- S. Rangarajan Etc vs P. Jagjivan Ram: In this case, the Court held that freedom of expression cannot be suppressed unless the situation so created are dangerous to the community/ public interest wherein this danger should not be remote, conjectural, or far-fetched. There should be a proximate and direct nexus with the expression so used.

| Govt. disagrees with India’s rank in World Press Freedom Index |

- India is ranked at 142 out of 180 countries on the World Press Freedom Index 2021.

- In the South Asian neighbourhood, Nepal is at 106, Sri Lanka at 127, Myanmar (before the coup) at 140, Pakistan at 145 and Bangladesh at 152.

- China is ranked 177 and is only above North Korea at 179 and Turkmenistan at 178.

- What the report said about India

- Criminal prosecutions: Often used to gag journalists critical of the authorities.

- Targeting women: It has been highlighted that the “campaigns are particularly violent when the targets are women”.

- Draconian laws: It termed various Indian laws such as – laws on ‘sedition,’ ‘state secrets’ and ‘national security’, draconian.

- Curb on freedom of expression: The report has also highlighted the throttling of freedom of expression on social media.

- Censorship on social media: It specifically mentioned that in India the “arbitrary nature of Twitter’s algorithms also resulted in brutal censorship”

- Reservations held by India:

- India along with many nations has reportedly disgusted the outcomes of this report. It stated that media in India enjoy absolute freedom.

- The government does not subscribe to its views and country rankings and does not agree to the conclusions drawn by this organization for various reasons:

- Non-transparent methodology

- Very low sample size

- Little or no weightage to fundamentals of democracy

- Adoption of a methodology that is questionable and non-transparent

- Lack of clear definition of press freedom, among others

| Recent Instances of Hate Speech in India |

- In December, the Haridwar Dharam Sansad took place, where the scale of hate speech got further intensified. The actors were unabashedly calling for violence against Muslims. Some of those comments bordered on genocidal calls. In fact, certain statements called for the replication of the violence unleashed against Rohingyas in Myanmar.

- The controversial Yati Narsinghanand, facing several FIRs in UP, called for a “war against Muslims” and urged “Hindus to take up weapons” to ensure a “Muslim didn’t become the Prime Minister in 2029.”

- The Supreme Court had yet another opportunity to address the issue of hate speech in a case against the TV programs which communalized the COVID pandemic with programs containing anti-Muslim content.

- In this case, the Court expressed disappointment with the affidavit filed by the Union Government by saying it was “extremely evasive and brazenly short of details”. The Court was unhappy with the revised affidavit filed by the Union as well.

|

A Case of Over-criminalisation of Speech

|

| Major Reasons for Hate Speech |

- Superiority Feeling :

- Individuals believe in stereotypes that are ingrained in their minds and these stereotypes lead them to believe that a class or group of persons are inferior to them and as such cannot have the same rights as them.

- Doggedness to Particular Ideology:

- The stubbornness to stick to a particular ideology without caring for the right to co-exist peacefully adds further fuel to the fire of hate speech.

- Negative stereotypes: The people who are negative stereotypes lead us to think of another individual as inferior and less worthy which creates a sense of hate speech and the reason why negative stereotypes occur is because of the systems of oppression – discriminatory structures, etc.

- Illiteracy: Lack of education prevents the overall development of an individual. Still, about 23% of the population in India is illiterate. This prevents the development of tolerance and understanding of individuality in them.

- Prejudice and bias: Bias toward a particular group can be a reason for hate crimes. E.g 704 cases of crimes against Northeast people in Delhi in 3 years. It can incite hate crimes against them without making any difference between culprit and innocent.

- Lack of strong laws: lack of strong and clear laws, poor implementation results in low conviction rate. So, culprits are left to roam freely.

- Vote bank politics: Often vote bank politics, use various communal or emotional tools to garner the vote of a few groups by inciting hatred in them. They use false stories, news, etc to incite such incidents.

| Challenges in regulating hate speech |

- Freedom to speech: Any regulations for social media content should follow globally accepted norms of freedom of speech and impartiality which is hard to apply with the restrictions on the content.

- Independent Regulator: An independent regulator can be misused in geographies where the idea of impartiality is used to the wish of the ruling regimes.

- Privacy Regulation: The introduction of privacy regulations such as the European Union’s General data protection regulation (GDPR) signalled the fact that the self-regulation of the platforms didn’t work in the desired way.

- Lack of social consensus against hate speech: No matter how precise and how definite we try to make our concept of hate speech, it will inevitably reflect individual judgment.

- In Europe, for example, holocaust denial is an offence – and is enforced with a degree of success – precisely because there is a pre-existing social consensus about the moral abhorrence of the holocaust.

| Way forward |

- Much of the existing penal provisions deal with hate speech belong to the preInternet era. The need of the hour is specialized legislation that will govern hate speech propagated via the Internet and, especially, social media.

- Reference can be drawn to the Australian federal law called the Criminal Code Amendment Act, 2019, which imposes liability upon Internet service providers if such persons are aware that any abhorrent violent material, which is defined to include material that a reasonable man would regard as offensive, is accessible through the service provided by them.

- Punitive action: The legislature and political parties should suspend or dismiss members who are implicated in hate crimes or practice hate speech. Strict disciplinary action should be taken against such individuals and parties.

- Code of conduct: the European Union has also established a code of conduct to ensure non-proliferation of hate speech under the framework of a ‘digital single market.’It requires collaborative, independent, and inclusive regulation that is customised to regional and cultural specifications while adhering to global best practices of content moderation and privacy rights.

- The Law Commission of India recommended that new provisions in IPC are required to be incorporated to address the issue of hate speech.

| Conclusion |

- Action commonly taken against modernday hate speeches have a whackamole effect wherein the underlying objective of inciting communal disharmony or hatred, despite the detention of the offender, survives through digital or social media platforms for eternity.

- Thus, taking a cue from best international standards, it is important that specific and durable legislative provisions that combat hate speech, especially that which is propagated online and through social media, are enacted by amending the IPC and the Information Technology Act.

- Ultimately, this would be possible only when hate speech is recognized as a reasonable restriction to free speech.

Recent Articles

- India-Canada Relations: A Comprehensive Analysis of History, Ups and Downs, and Current Challenges

- World Heritage Sites in India Under Threat: A Recent Overview

- 100 Most Important Topics for Prelims 2024

- Most Important Tribes in News 2024

- Most Important Index in News 2024

- Geography 2024 Prelims 365

- Government Schemes & Bodies 2024 Prelims 365

- Society 2024 Prelims 365

- Economy 2024 Prelims 365

- Polity 2024 Prelims 365

Popular Articles

- UPSC CSE 2023 Mains Essay Paper Model Answers

- UPSC CSE 2022 Mains GS 1 Paper Model Answers

- Storage, Transport & Marketing of Agricultural Produce & Issues & Related Constraints.

- Static Topics Repository for Mains

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- UPSC CSE 2023 Mains GS 1 Paper Model Answers

- UPSC CSE 2022 Mains GS 4 Paper Model Answers

- UPSC CSE 2023 Mains GS 2 Paper Model Answers

- PDS: objectives, functioning, limitations, revamping

- Achievements of Indians in Science & Technology

Popular Topics

ART & CULTURE

CASE STUDIES

COMMITTEES & SUMMITS

DISASTER MANAGEMENT

ECONOMICS

ECONOMICS PREMIUM

ECONOMICS STATIC

ECONOMIC SURVEY

EDITORIAL

ENVIRONMENT & ECOLOGY

ENVIRONMENT PREMIUM

ETHICS

GEOGRAPHY

GEOGRAPHY PREMIUM

GEOGRAPHY STATIC

HEALTH

HISTORY

HISTORY PREMIUM

HISTORY STATIC

INDIAN POLITY

INDIAN POLITY PREMIUM

INDIAN POLITY STATIC

INTEGRITY & APTITUDE

INTERNAL SECURITY & DEFENSE

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

LITE SUBSCRIPTION PREMIUM

MAINS

MAINS CORNER PREMIUM

PLUS SUBSCRIPTION PREMIUM

POLITY & GOVERNANCE

PRELIMS

PRELIMS CURRENT AFFAIRS MAGAZINE

PRO SUBSCRIPTION PREMIUM

REPORTS

SAMAJHO'S CORNER PREMIUM

SAMAJHO ANALYSIS

SAMAJHO CORNER PREMIUM

SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

SELF PREPARATION

SMAP ANSWER WRITING

SOCIETY

SPR

SYLLABUS

TELEGRAM

YOJANA GIST